Winter can be a beautiful time to paddle, but cold water is also extremely dangerous. Dream Team member and Canadian expedition paddler Bruce Kirkby shares what it takes to be prepared for any condition…

To begin, ‘cold’ is a relative term, and there is no set temperature (of either water or air) when paddleboarding abruptly becomes ‘cold weather’ paddleboarding. Rather, hypothermia–the potentially fatal cooling of body core temperatures–remains a serious danger that can sneak up at any time, even on sunny spring and fall days. But for this blog post, we will focus on winter paddling.

Factors affecting how quickly a body loses heat include water temperature, air temperature, wind speed, time of day, the strength of sun, along with activity and energy levels of the paddler. A good question to ask yourself before setting out for any paddling session: if you fell from your board at the furthest point of your route, could you return to the starting point and remain warm? If unsure, either take more clothing or don’t go.

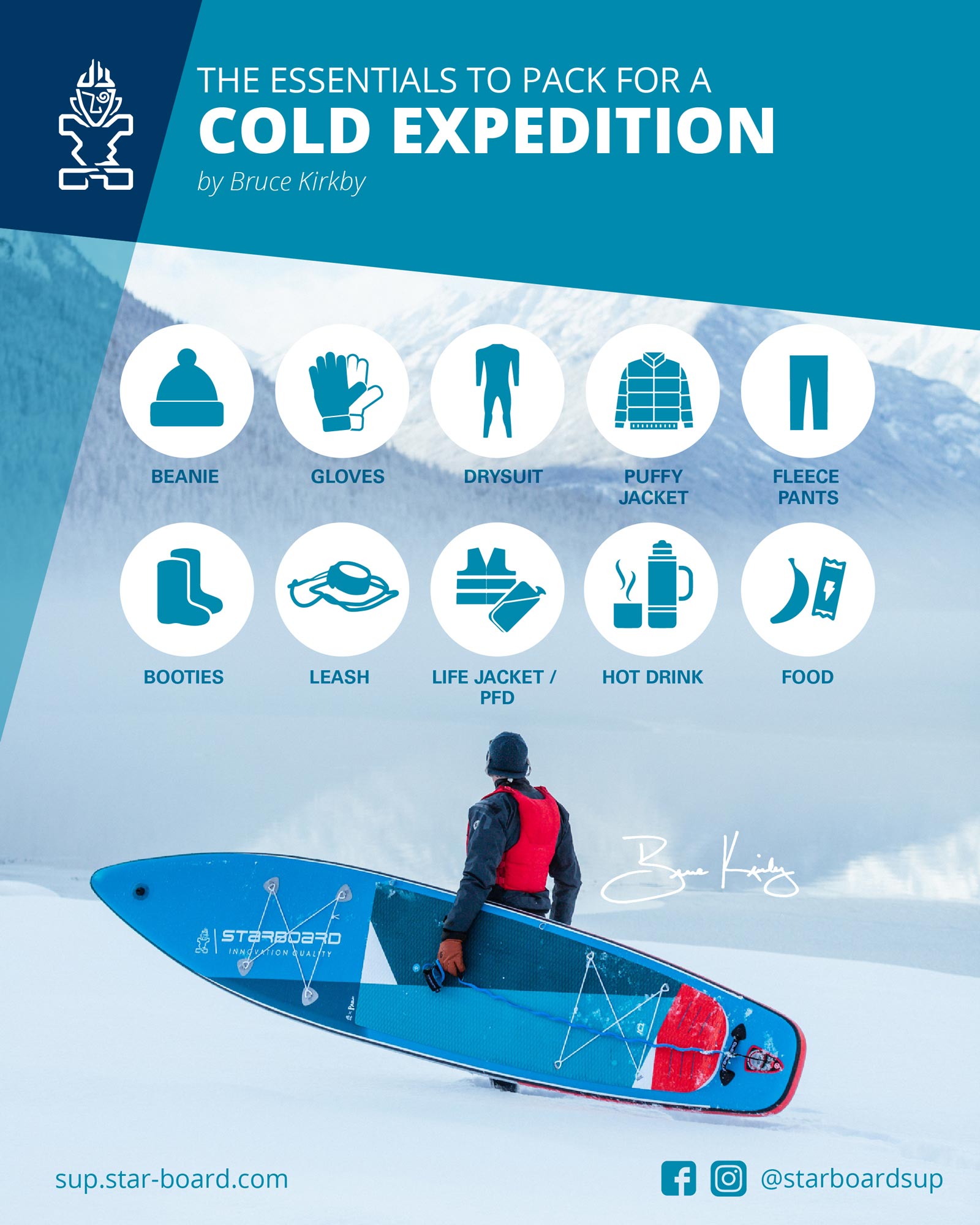

Wetsuits are typically limited to temperatures above freezing (their warmth based on thickness), so when snow is on the ground, a drysuit becomes essential. Additional layers of insulation must be worn beneath any drysuit, and the cooler the day, the more layers you should wear. It is important to always wear synthetic or wool layers, and never cotton. Synthetic and wool both provide warmth when wet, while cotton cools–and can ultimately kill.

Hands, feet and head require special attention in cold weather.

Gloves are essential. I like to use rubber-coated work gloves (cheap and available at most hardware stores) and I always bring a spare pair along, in a drybag, as gloves usually get damp with time from handling the paddle.

A warm wool or synthetic hat is crucial (no ball caps please) for the head represents a significant source of heat loss. Always keep a spare hat handy, so if you fall into the water, you can quickly pull a dry hat on.

Keeping feet warm can pose a challenge. Drysuits that include integrated socks offer the best protection, allowing a paddler to wade into water up to their neck without a drop getting inside their suit. I wear thick, warm socks inside my drysuit socks, and protective, insulating booties over top. An alternative (for drysuits without integrated socks) is to wear thick wool socks covered in plastic bags (which are tucked inside drysuit ankle gaskets), and then booties overtop.

Always carry additional warm clothes—like a puffy jacket and fleece pants–in a dry bag. You can change into these after paddling, or in case of an emergency. A warm drink and high-energy snack are also a good idea, as both can rewarm a cool paddler.

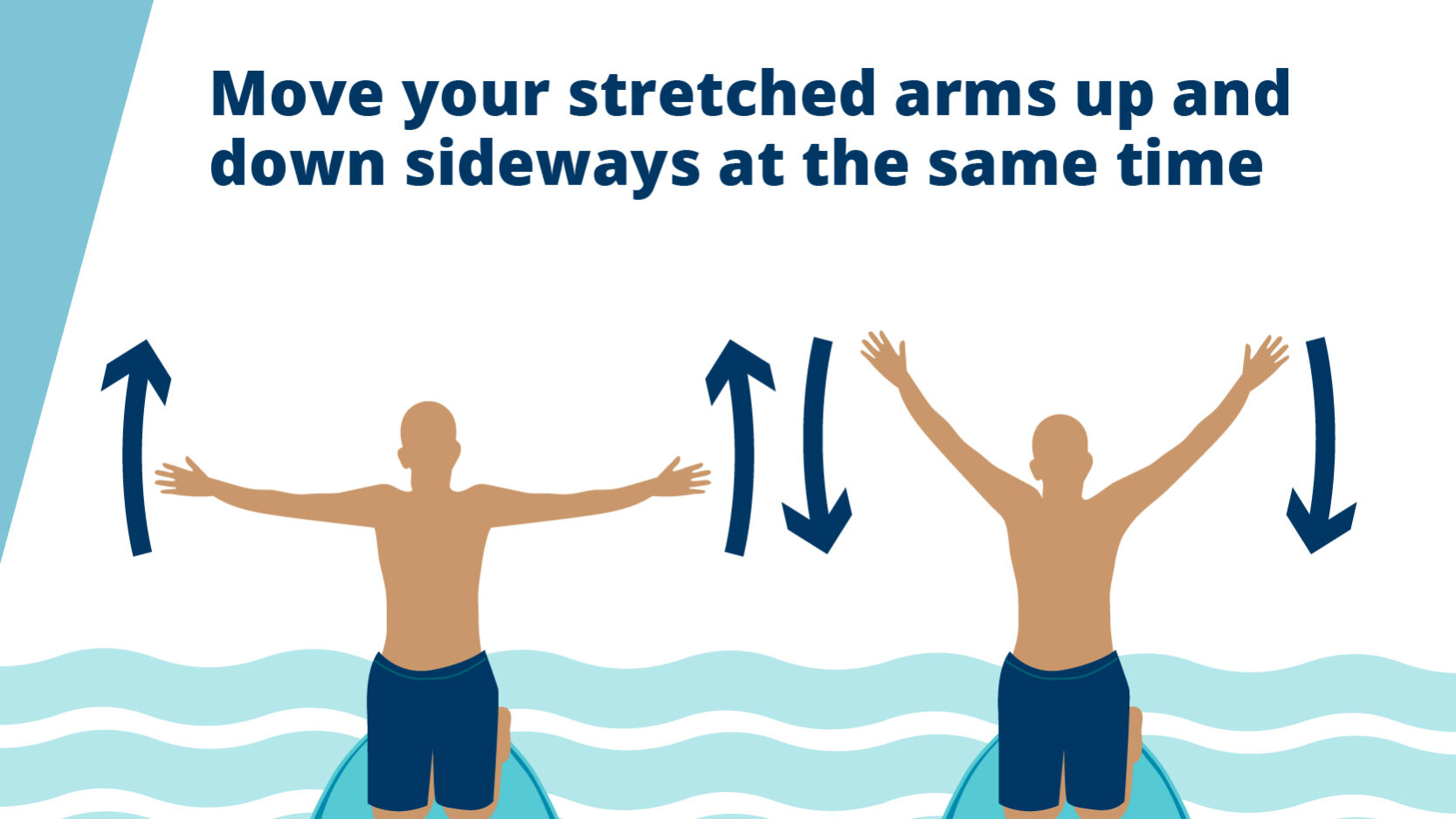

Finally, ALWAYS paddle with a partner in cold weather. If either of you fall in, is essential to act as quickly as possible, helping the wet paddler get out of any damp clothing and into dry gear. Afterwards, jump around or swing arms vigorously if necessary, to rewarm. There is only a limited window before you begin to lose dexterity and mental acuity—then hypothermia sets in.

Despite these warnings, cold weather offers profound rewards to the prepared paddler. Nature serves up a special beauty during the depths of winter. But please remember, cold water can be deadly. If you are new to winter paddling, please begin slowly and cautiously. Make conservative plans. Don’t try to set speed or distance records. Prepare meticulously. Paddle with more experienced mentors. And always place safety first.