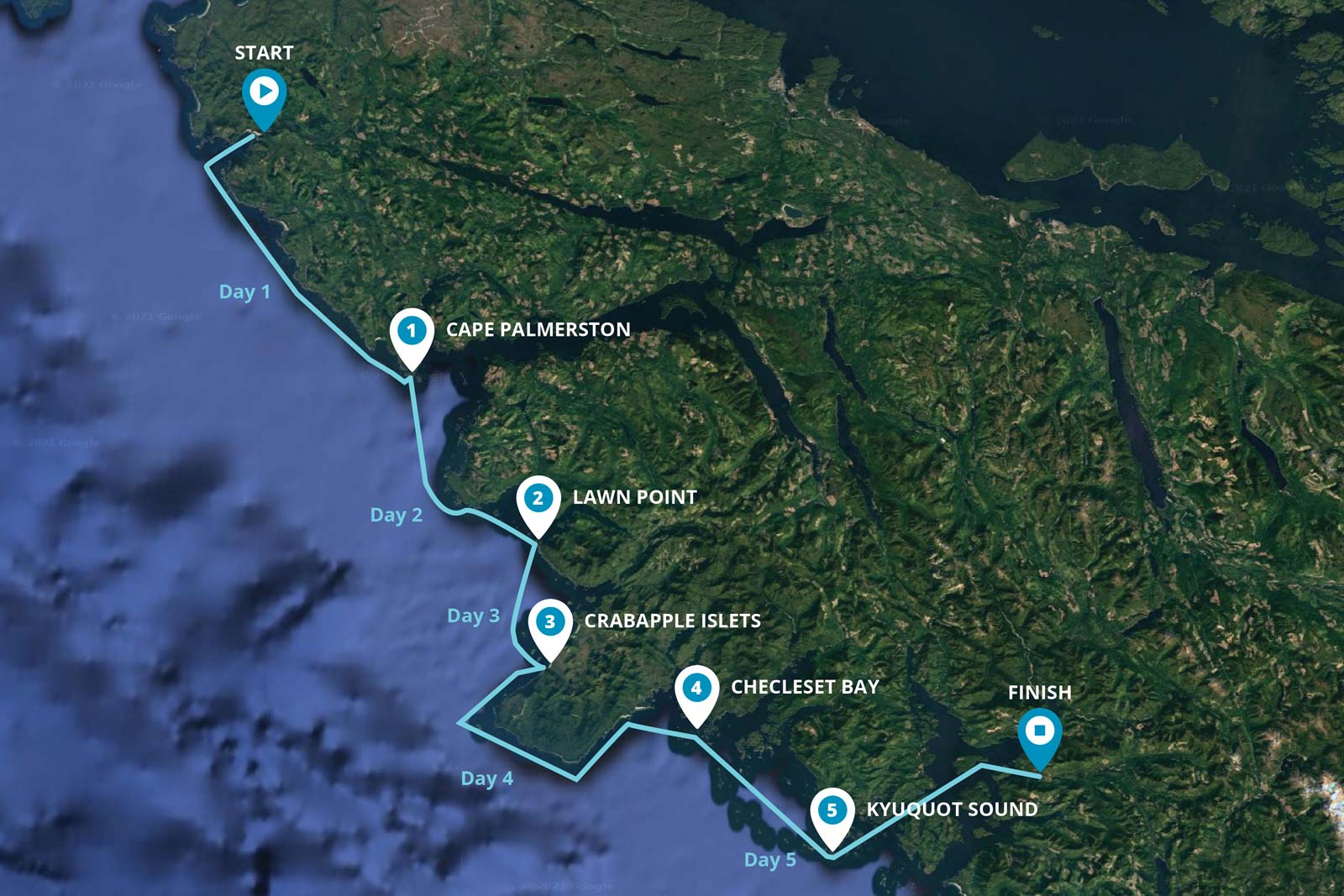

This August, adventure stand-up paddle boarder and photographer Bruce Kirkby, alongside expedition partner Norm Hann, set off aboard fully-loaded expedition paddleboards in an attempt to round Canada’s notorious Brooks Peninsula, off the east coast of the Cape Scott Provincial Park.

Jutting far into the open Pacific, the Brooks Peninsula is the most westerly point on Vancouver Island which amplifies winds, currents, swell and storms. The site of many shipwrecks, it is considered among the most challenging portions of the British Columbia coastline. No one was certain if it had been rounded by SUP previously.

Here is the day-by-day recount of their 5-day SUP expedition, in Bruce’s words;

San Josef Bay to Quatsino Sound (47 km)

DAY ONE

After loading our boards with almost 100 lbs of food, water and gear, Norm and I paddled a lazy, tidewater river towards the outer sand beaches of San Josef Bay. Punching through waist-high surf, we turned south and were swept on by building northwesterly winds.

Travelling far offshore, we passed the rocky shores of Cape Palmerston. A storm had passed recently, and the seas remained confused and lumpy. We passed two ocean sunfish, or ‘mola mola’ as they are known locally, extraordinary creatures that can exceed 8 feet in length and grow to over 1000kg (2200 lbs).

After six hours of tiring paddling, we slipped into the protected waters of Quatsino Sound—thrilled that the expedition was finally underway, yet aware that the greatest challenges still lay ahead.

Quatsino Sound to Heater Point (27km)

DAY TWO

Launching at dawn, we paddled across the wide mouth of Quatsino Sound, into darkening skies and building swell.

By the time we reached Lawn Point, the seas had grown to 3 metres. Dark waves heaved themselves skywards, then collapsed along the rocky shores, the sound of crashing surf booming across the waters. A coast guard cutter appeared, then soon vanished behind, and we wondered if they even saw us–a reminder of just how tiny we were amid the vast ocean.

Norm vanished regularly, lost behind lumps, reappearing below me in a trough or balanced against the sky above. A wane sun-kissed the waters, but the day grew blustery. Alone with our thoughts, tossed by waves and wind, the situation never felt dire. But during those hours, my mind never wandered either, not for a second. We had entered a state of hyper-awareness or constant vigilance; understanding that while the situation may be manageable, things could change quickly. Best to pay attention.

Beyond the mouth of Klaskino Inlet, we took shelter in the lee Heater Point, landing in surf. The landscape now was wild and windswept, and it felt as if we’d passed through a portal. There was no going back now-Lawn Point had proved more than we’d bargained for in these rugged seas. The only way out was onwards.

Heater Point to Crabapple Islets (18km)

DAY THREE

Thankfully the ocean settled overnight… a bit. With warm sun and clearing skies, we set off towards the Crabapple Islets — the final possible landing point, and strategic launch site for paddlers hoping to round the Brooks.

Landing on a windswept beach just after 10 a.m. we spent the rest of the day relaxing, eating and beachcombing. A pack of wolves had passed hours earlier, the prints yet unaffected by rain and shifting sand. The landscape was primal; massive trees and house-high salal (bush) blown into tortured shapes by constant wind and storm.

We would rise before the sun the next morning, planning to catch an ebbing tide around the Brooks. Our VHF radio announced favorable NW winds would bless us for two days. But on the third morning, gale force south easterlies would arrive-heralding the first autumn storm. If everything went according to plan, we could slip around the Brooks and race down the coast to the safety of Kyuquot Sound before the ocean turned untravelable. But the window was tight, and many challenges still lay ahead.

We fell into a fitful sleep with the tent shaking in 25kn winds and the ocean around us a sea of whitecaps.

Crabapple Islets to Acous Peninsula (42km)

DAY FOUR

Up in darkness, we brewed coffee and oatmeal, loading the boards as dawn broke. Conditions looked good, but a sense of gravity marked our launch-the route ahead was committing.

Mquqin — as the Brooks Peninsula is known to Che:k’tles7et’h’ people—means ‘The Queen’. To the Koskimox, it is ‘Where the Wind is Born.’ Captain Cook described it as the ‘Cape of Storms.’ Perfectly rectangular, it juts far into the Pacific, dividing weather systems on Vancouver Island. Its 10 km wide headland is delineated by Cape Cook to the north and Clerke Point on the south.

The first two hours passed quickly. With low swell, we tucked inside the offshore reefs, working ourselves steadily westwards. Sunlight sparkled off undulating waters, while the Brooks lingered in shadow.

Suddenly the dark cliffs of Cape Cook reared before us, skyline crowded with Sitka spruce. Three enormous dark waves rose and passed beneath us. Beyond lay beds of bull kelp, the scale of which I have never witnessed before. Then Solander appeared, kissed by the morning sun. This craggy, pyramidal island–an internationally significant seabird sanctuary–lies 1.5 km off the tip of the Brooks and looks like it belongs on a Star Wars set.

For a short time, we stood silently, trying to drink the moment in, balanced at this rarely-glimpsed precipice of extraordinary beauty that we both knew we might never return to. Also, a place capable of sudden and unspeakable ferocity.

There was no time to linger. It was only 8-o-clock, but already winds were gusting to 25 knots. Without a backwards glance, we pointed our boards south, and focused on the task at hand.

Two hours later, a building ebb and NW winds had carried us past the reefs of Clerke Point, into the relative safety of Checkleset Bay. We stumbled ashore on the sand beaches of Jacobson Point, devoured a lunch of cheese and pepperoni, then carried on towards the tranquil islets of the Acous Peninsula.

Acous Peninsula to Spring Island

DAY FIVE

With the tension of the Brooks behind us, we enjoyed a leisurely day crossing the calm waters of Checklesat Bay, passing sea otters, porpoises and countless jellies. At the lonely Thomas Islets, Norm spotted a dead humpback on a secluded beach, and stopped to strap an enormous rib bone (80 lbs and shoulder high) on the back of his paddleboard–a gift for his son!

With a SE storm bearing down on the coast, we took refuge at a sea kayaker’s basecamp on Spring Island. The next morning we caught a boat ride to Fair Harbour, where our friend Neil Gilson was waiting with a truck to drive us home, and a dizzying mix of rum of other spirits.

For several summers, Norm and I have tackled increasingly challenging paddleboard expeditions–sure, because we love being out there, but also because of a shared desire to build awareness of paddleboards’ extraordinary capabilities and strengths in serious expedition settings. It has been rewarding for both of us to share what we’ve learned on these journeys. I will post packing tips and lists soon, but in the meantime, please don’t hesitate to ask if you have any questions.